The Republic (literature)

| |

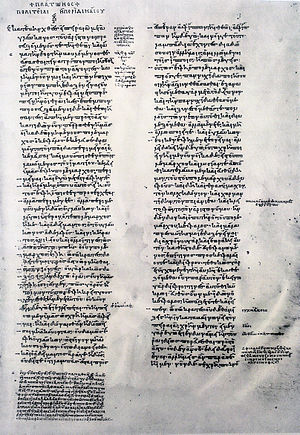

| Original Title: | Πολιτεία |

|---|---|

| Written by: | Plato |

| Central Theme: | Contemplations on justice |

| Synopsis: | |

| Genre(s): | dialogue |

| First published: | circa 375 BCE |

Describe The Republic here.

Oh, no, no. If I do that, you'll just twist my words around and make me look silly.

Well, if you insist. The Republic (Πολιτεία -- Politeia) is perhaps the most well-known dialogue of the ancient Greek philosopher Plato, offering profound contemplation on the meaning of justice, and whether the just or the unjust man is happier in life. The work is split into ten separate books, making it one of Plato's longer pieces. Like most of Plato's dialogues, The Republic centers on Plato's teacher, the celebrated Socrates. The other characters in the dialogue are Glaucon, Polemarchus, Cephalus, Thrasymachus, Adeimantus, and Cleitophon. Of these, the chief characters are Glaucon and Adeimantus (incidentally, Plato's older brothers); the others speak little –if at all – beyond the first book. Others are present, but do not speak during the dialogue.

The dialogue begins as Socrates and Glaucon are invited to a gathering at the home of Polemarchus. Upon arrival, Socrates begins conversing with Polemarchus’s father Cephalus. During this talk, Cephalus comments upon the benefits of justice, prompting Socrates to pose the question for which he is probably best remembered: “What is justice?” Cephalus (perhaps wisely) excuses himself from the discussion at this point, and it is taken up by Polemarchus and later Thrasymachus, who each have their own definitions of justice. Socrates responds with his renowned Socratic Method: instead of openly contradicting their definitions, he asks a series of questions regarding their specifics until their inherent contradictions become apparent. Polemarchus soon abandons his definition, and though Thrasymachus is regarded as one of Socrates’s more formidable opponents, he eventually does likewise.

When Thrasymachus yields, Glaucon and his brother Adeimantus take his place, not convinced by Socrates’s reasoning. Socrates therefore suggests a bold thought experiment: the three of them will devise a hypothetical society which is perfectly just and analyze what makes it just, then deduce from there what justice means. The rest of the dialogue is dedicated to the conception of this hypothetical republic, as Socrates describes it in minute detail and goes to great lengths to explain his reasoning. Along the way, Socrates determines that a just society is one in which each individual concerns himself with his own business and no one else’s, that a just person is one whose emotions do not overwhelm his reason, and that acting justly leads to happiness while acting unjustly leads to unhappiness.

Socrates's idea of a perfect society may not sound so great to modern audiences, but it isn't his conclusions so much as his process that makes The Republic so interesting. Socrates is logical and methodical. He is concerned less with coming to an answer quickly than with coming to the correct answer in the end. He considers no detail obvious or unimportant, and examines everything. And most strikingly, he doesn't allow himself to get carried away, constantly pausing to make sure that his friends agree with his reasoning. This is Socrates in all his humble glory, providing a shining example for students of philosophy even today, and that is why The Republic has endured as a philosophical masterpiece for so many centuries.

You can read a translation at Wikisource. (They got it from Project Gutenberg.)

- Author Avatar: When you consider that no one is really sure whether it was actually Socrates or Plato who wrote the book... From a literary perspective, the two philosophers are actually considered the same person. This trope is in play with Socrates as the main character and Socrates/Plato as the author.

- The Cynic: Thrasymachus. He even believes that Justice protects the interests of the strong over the weak.

- Day Hurts Dark-Adjusted Eyes: used in the Platonic Cave description

- Democracy Is Bad: Socrates believes it is one step away from tyranny. However, the "democracy" that Western audiences are familiar with is actually a democratic republic, which uses elected representatives to create layers and sections of government that act as failsafes for one another. The democracy that Socrates knew was just this side from mob rule, and could be easily leveraged to bring about a dictatorship.

- Fanfic/Real Person Fic: Most of Plato's works amount to fanfics of Socrates's life, but that being said...

- Fantastic Caste System

- Genre Savvy: At one point, Socrates is leading the conversation in his usual manner, and Adeimantus notices. He proceeds to interrupt the conversation and demand that Socrates stop pretending to be a moron and simply state what he's trying to get at.

- Good Feels Good: A just man is happier than an unjust man.

- I Just Want to Be Normal: During the Myth of Er, when the departed souls are given the opportunity to select their next life, Odysseus searches for the most uneventful, simple life he can find.

- Invisibility: The Ring of Gyges parable.

- Might Makes Right: Thrasymachus is all over this trope.

- Perfect Pacifist People: The hypothetical republic embraces pacifism... for the most part.

- Platonic Cave: The Trope Namer

- Totalitarian Utilitarian: The way in which Karl Popper interprets Plato as the author of this dialogue.

- Utopia: The point of the dialogue is to define one.

- Utopia Justifies the Means: Some of the utopia's laws are actually horrifying by today's standards.

- With Great Power Comes Great Insanity: Socrates claims that philosophers make the best rulers because they can avoid this.

- Yes-Man: All the other characters there amount to saying "Yes, Socrates, you are right" after everything Socrates says.